Europa

The evolution and fate of shallow water on Europa

The surface of Europa’s outer icy shell is littered with dark circular features, roughly 10 km (6 mi) in diameter, as seen in the image above (NASA photojournal image PIA03878). They appear to either uplift, depress, or completely break up the surface, but how they form is not currently clear. One hypothesis suggests that they are formed by lakes of salty water perched within Europa’s ice shell at 1-2 km (roughly 1-2 mi) below the surface. If true, how long these briny environments survive in the subsurface and how they evolve along the way is important for understanding Europa’s ice shell and ultimately its ability to support life. To try to answer these questions, we used numerical modeling techniques based on the physics of freezing solutions constrained by terrestrial analogues and observational evidence of Europa.

We found that they are relatively short lived on geological timescales, with liquid water surviving beneath the surface for less than about 100,000 years. Some geological evidence suggests that the depressions may be the youngest of this feature class, and so together with our results may suggest that large brine reservoirs may still be present beneath Europa’s surface. Furthermore, salt leftover in the ice (seen in right panel the animation below) can make distinct chemical zoning patterns and even possibly leave behind layers of salt precipitated during freezing. Together, these processes may be important for geophysical processes in the ice shell and could be detectable by future missions such as Europa Clipper or ESA’s JUICE.

You can read about this work here

Above is an animation of results from our study where the top of each panel is Europa’s surface and the bottom is the bottom of Europa’s brittle ice layer and the x-axis denotes the distance from the center of the reservoir. This animation illustrates of the evolution of the temperature (left panel), water content (middle panel; blue is water, white is ice), and salt content (right panel; concentration is in parts-per-thousand, or grams of salt per kilogram of solution) of a salt water reservoir in Europa’s ice shell.

# Stable brine layers beneath Europa’s chaos terrain

The formation of Europa’s chaos terrain, large regions where the surface has completely broken up and exemplified by Conamara Chaos seen above (NASA photojounral image PIA03002), has puzzled planetary scientists since the Galileo mission arrived. One hypothesis proposes that salty ices allow the interior of the ice shell to melt large volumes of water just a few kilometers below the surface creating a “melt lens.” How long does this melt lens last in the subsurface and how does it evolve over time? We update the numerical model from the previous work to investigate.

The formation of Europa’s chaos terrain, large regions where the surface has completely broken up and exemplified by Conamara Chaos seen above (NASA photojounral image PIA03002), has puzzled planetary scientists since the Galileo mission arrived. One hypothesis proposes that salty ices allow the interior of the ice shell to melt large volumes of water just a few kilometers below the surface creating a “melt lens.” How long does this melt lens last in the subsurface and how does it evolve over time? We update the numerical model from the previous work to investigate.

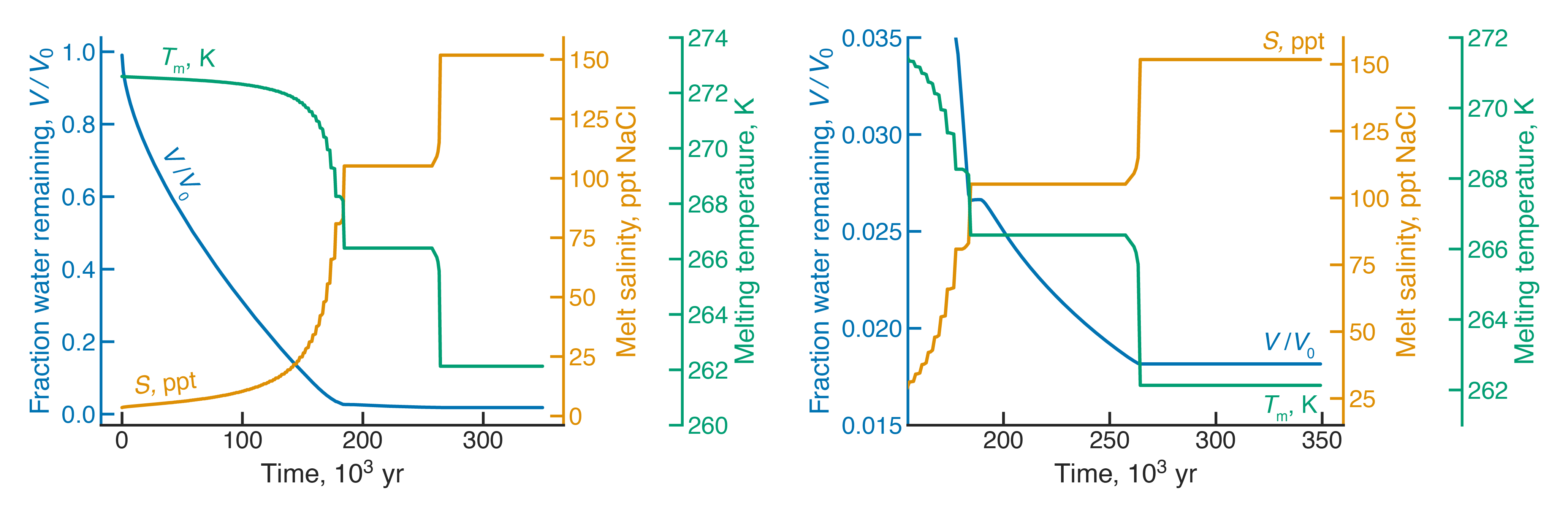

We found that in a lower bound, a large melt lens without any salt would last at least 175,000 years beneath the surface – almost 30,000 years longer than the longest lasting small reservoir that includes salt. When the melt lens includes even a small concentration of salts (less than 1% by weight), the process of cryoconcentration of salts will not only make the remaining melt highly saline, but also stall freezing for potentially 100s of thousands of years (see the figure below). This could mean that highly saline brine layers are stable against freezing a few km below the surface on geological time scales.

If these large chaos features form by these melt lenses and are among the youngest features on the surface as the evidence suggest, then we suggest that missions to Europa such as NASA’s Europa Clipper or ESA’s JUICE will find evidence for contemporaneous brine layers beneath chaos. Moreover, as these potential brine layers are relatively close to the surface they may be a realistic target to sample a potentially habitable environment for future missions planning to drill (or melt) through the ice shell.